If you’re wearing a mechanical watch right now, it’s likely running on the magic of two tiny—but mighty—components: the balance spring and the lever escapement. They’ve been quietly doing their thing for centuries, keeping time on track while you take all the credit. Think of them as the watch world’s ultimate power couple—small, springy, and absolutely essential.

Pursuing portable accuracy

Today’s leading manufacturers use state-of-the-art gear to shape these two parts into fine timekeeping instruments. When someone asks me, ‘Why are luxury watches so expensive?’ I usually point to the incredible micro-engineering it takes to build movements that stay precise no matter the conditions. Many of these advancements are so subtle they go unnoticed by the wearer—yet they mean everything to the manufacturer in the relentless pursuit of precision.

While one end of the industry relies on a high-performance lever escapement, the other end uses a more rudimentary version. Although the latter comes with a lighter price tag, it’s still a combined effort of a balance spring (commonly referred to as a hairspring) and lever escapement delivering stunning precision. And the difference between both types is a matter of just mere seconds per day. That’s the beauty of modern watchmaking—even the more affordable luxury brands, backed by movement giants like Sellita and ETA, are offering remarkable accuracy. What we now see as routine mechanical accuracy—especially in portable watches—was once a near-impossible feat, hard-won by generations of horological pioneers.

So when did this perfect pairing of hairspring and lever escapement first hit it off—and who gets the bragging rights? Let’s begin in the seventeenth century.

Hairspring (circa 1675)

While the seventeenth century was fraught with social and political upheaval, it was also an era of deep scientific discovery that included the Scientific Method, Galileo’s solar-centered universe theory, Isaac Newton’s law of gravity, the invention of the microscope, and even construction of the Palace of Versailles. The innovative spirit of this time also treated us to two critical watchmaking innovations – the pendulum and metal balance spring (commonly referred to as the ‘hairspring’).

When the first tower clocks emerged in 14th-century Europe, a balance wheel and escape wheel worked in tandem to drive massive iron gears that groaned and clanked out the time. Erected in town squares and high traffic areas, these earliest timekeepers only chimed the hour. Their high visibility meant everyone regardless of social class had access to this information. Mechanical timekeeping at this stage was very young, and so the machinery within was not of the accurate type we’re used to today. However, they did contain a balance wheel and an escape wheel.

But wait—how could that be, when the hairspring only made its debut in 1675? Hold tight, because I’m about to unravel the mystery.

Once upon a time, the profession of watchmaker didn’t exist, and so this work was performed by scientists, inventors, locksmiths, blacksmiths, goldsmiths, and other trades. These tradesmen had taken on the monumental task of miniaturizing the mechanics of tower clocks. In the fourteenth century the craftsmen constructing tower clocks weren’t thinking about future wristwatches and pocket watches. Their main goal was to bring timekeeping indoors—and thanks to Christiaan Huygens, his invention of the swinging pendulum made that possible in 1656. What an exciting moment this must have been.

Imagine the day your very own grandfather clock arrived – these were hot items to have – and how good it must’ve felt inviting your friends over to gaze upon its beauty. I picture everyone gathered in the living room watching the pendulum, its hypnotic side-to-side motion aided by the mysterious forces of gravity, its signature tick-tock sound of the escapement at work possibly sparking conversation about its cutting-edge technology. And yet, the arrival of the hairspring would upstage it.

Although the pendulum was the most accurate clock the world had ever known at that time it was still far from perfect. Lacking both accuracy and mobility, there was a clear opportunity for something better — and once again, it was Christiaan Huygens who seized it. This time, however, he faced competition from the scientist, architect, and polymath Robert Hooke, who was also chasing a solution. The clash of their efforts sparked one of watchmaking’s most enduring debates: Who, beyond all doubt, truly invented the balance spring?

Over time, strong and convincing arguments arose supporting each of these men as the true creator of the balance spring we know today. A study done by Rob Memel presents a case, that I believe, makes it difficult for any Robert Hooke fan to refute. The one point scholars from both sides agree on is that Hooke and Huygens were independently pursuing similar solutions to the same problem, right alongside each other. This is substantiated by each of the mens’ own journal entries. According to Memel’s study, while Robert Hooke struggled to produce a working model, Christiaan Huygens succeeded in developing the first functioning balance spring.

As fascinated as I am by this piece of history, right now I’m less focused on who invented the balance spring and more captivated by the profound impact it had on timekeeping—and how it helped launch the modern watchmaking industry we know today. That’s what this piece is about.

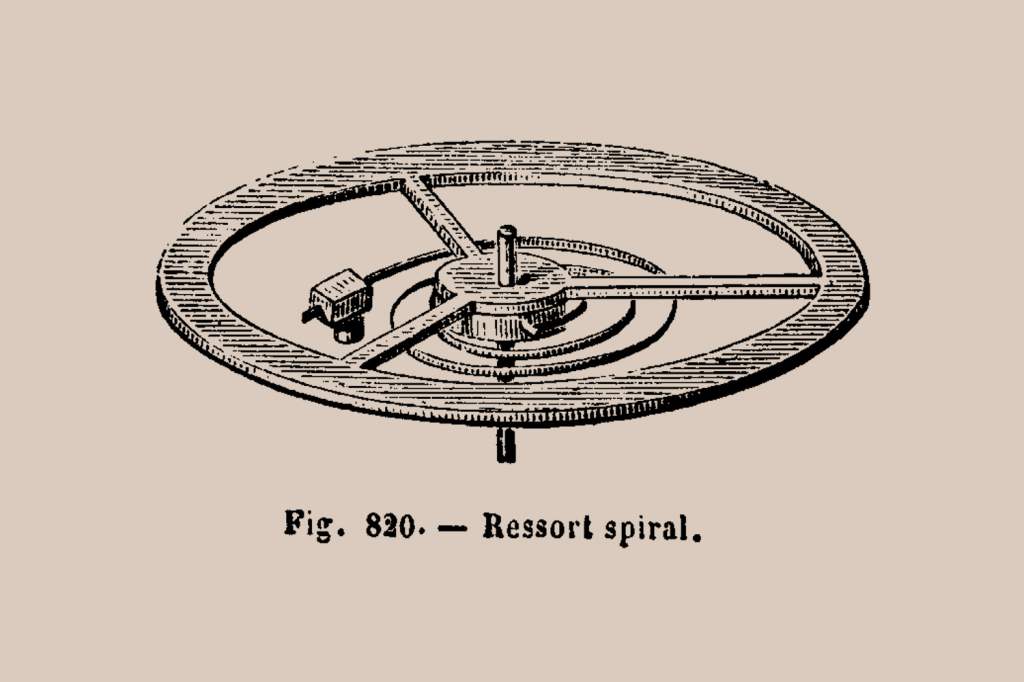

In 1675, the delicate hairspring—a slender coil of metal—stood poised to challenge the mighty pendulum and prove itself worthy of rewriting the rules of timekeeping forever. In the case of Robert Hooke’s own law of elasticity, he understood quite well that a metal hairspring expanding and contracting concentrically (“breathing”) in a rhythmic pattern would drastically improve accuracy. I first learned to appreciate the magic of a concentric unfurling of a balance spring during my time at Patek Philippe—where precision isn’t just taught, it’s ingrained. The ongoing work within the Maison continues to lead to discoveries. Going back nearly three and a half centuries, we would find these early inventors forming these early springs from a flat steel spiral of one and a half to two turns. The inner end of the coil was pinned to a brass collet fitted to the balance staff while the outer end was pinned to a stud fitted to the watch plate. And, they were adjustable! By sliding curb pins to lengthen or shorten the active length, you could speed up or slow down the rate of the watch. So, this ingenious design delivered precision and was easy for watchmakers to regulate – how brilliant.

By 1680, hairsprings had become common, flowing into new watches and even being retrofitted into older models with verge escapements. But simply integrating hairsprings onto verge escapements was just the beginning—it wasn’t enough to truly transform timekeeping.

A movement with a balance spring alone can achieve impressive precision, but when paired with an equally capable escapement, it reaches entirely new heights. Unfortunately, in the seventeenth century, the only escapement available for spring watches was the verge escapement. Though scaled down from its original tower clock size, it still had several limitations that hampered accuracy and reliability.

Despite its notorious flaws, the verge escapement improved dramatically when fitted with a hairspring. In fact, a high-quality verge equipped with a hairspring can keep time within 3 minutes per day—while the same escapement without a spring can vary by as much as 20 minutes daily. Just imagine if Christiaan Huygens’s balance spring was paired with an equally competent escapement.

Just imagine the revolutionary leap if Christiaan Huygens’s balance spring could pair with an escapement equally brilliant—a union that could forever change the course of timekeeping.

Detached Lever Escapement (circa-1754)

The hairspring’s perfect dance partner would finally arrive in 1754 thanks to Englishman, Thomas Mudge. Just as society was liberated from the pendulum, Thomas Mudge made sure poor timekeeping would be a thing of the past by ending our dependence on the verge escapement once and for all. His detached lever escapement is truly one of the most defining breakthroughs in watchmaking.

Friction is the fiercest villain in a mechanical watch movement. As a watch is steadily ticking, it’s steadily dying at the same time. Friction eating away the tiny components. One may think that simply adding lubrication would reduce the friction and the movement would gain life, right? Not exactly.

To this day, manufacturers are quietly working to reduce friction using the finest equipment in the world. It’s a multi-faceted problem because the answer we’re striving for isn’t one extreme or the other – it’s in the middle. Periodically, solutions emerge, are tested, and discarded as they often carry another obstacle with them. And so, work continues to find the ever- elusive middle.

The high friction doomed the verge escapement, even after it was scaled down enough to fit inside watches. Its design required the escape wheel to remain constantly locked against the balance wheel – creating an incurable rate of friction. As I noted earlier, this was improved by installing the hairspring, but Thomas Mudge would show the world that it had no place in modern watchmaking.

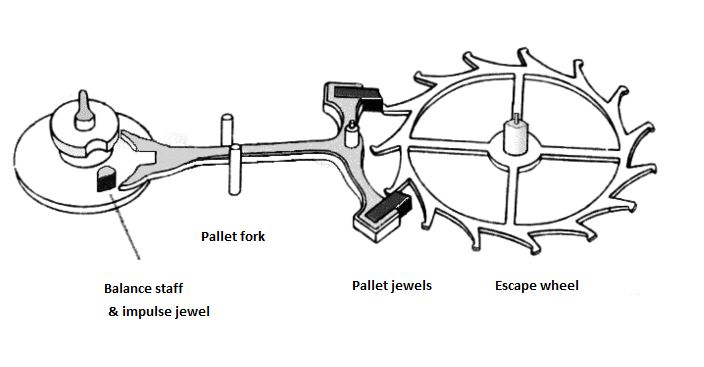

So, as an inventor and clockmaker, Mudge developed his detached lever escapement – called ‘detached’ as the escapement is cleverly separated from the balance wheel – leaving it free to perform its critical oscillations with less interference. Now, the balance wheel and escape wheel only interact with separate ends of a lever placed in between them, resulting in brief contact time thereby producing minimal friction. This mechanism crowned Thomas Mudge as watchmaking royalty, and fittingly the first watch endowed with this “crown jewel” of an escapement was for Queen Charlotte in 1770. Teamed up with Christiaan Huygens’ hairspring, this timepiece isn’t just any watch—it’s a superstar of horology and still proudly shines in the Royal Collection!

How do they work together?

Once the mainspring is wound by the crown, the energy would be transferred very rapidly and all at once to the dial hands if it were not controlled. So, the energy needs to “escape” progressively by a step-by-step escapement, consisting of the lever and an escape wheel with a unique profile.

The lever is knocked back and forth by a pin fixed to the underside of the oscillating balance wheel. As the wheel oscillates, the pin flicks the lever back and forth repeatedly. At the other end of the lever, the pallets block and release one tooth of the escape wheel with each flick. Each impulse delivered by the pin against the lever creates the signature “tick-tock” sound. With each oscillation of the wheel, the hairspring recoils, pulling it back in the opposite direction. This repeated motion turns the gears of the machinery to advance the dial hands.

Right now, I have a hairspring and escapement both made of silicon inside my wristwatch made in the 2000s. Peering through the sapphire caseback – like a portal to an artisanal past – I watch these two brainy concepts at work.

It’s so seductive that you forget they are scientific solutions to some of the greatest timekeeping problems in history. Although modern iterations are more refined, the crude examples from earlier times are no less attractive in my opinion.

My final thought

The mainspring gave us portable timekeeping, while the balance spring made portable timekeepers more accurate. Experts claim, and I would agree, that it formed this industry as artisans and craftsmen began dedicating their careers to watchmaking. These early watchmakers became indispensable—because with the arrival of the hairspring, timekeeping had entered a new era, and for the first time, the world demanded a minute hand. I think Christiaan Huygens would be thrilled to see his spring still working today; Robert Hooke would be surprised to know that his theory has endured for 350 years. It is still improving thanks to the development of alloys and silicon technology across the industry – like that of Silinvar® created by Patek Philippe.

As for the lever escapement—just how big of a deal was it, really? Well, even Thomas Mudge wasn’t totally sure at the time. He admitted as much in a modest letter to one of his patrons. But I’ve got to believe he’d be incredibly proud to know that his invention is now found in nearly every mechanical watch made today. Although it evolved in the nineteenth century, I believe he would still clearly recognize it.

These inventions didn’t just change time—they changed the world. They paved the way for the mechanical wristwatches we adore today, letting these little marvels of engineering tag along on our travels and share in life’s most unforgettable moments. Here at Thoughtful Collector, we’re raising a toast to the breakthroughs that made it all possible—and to the brilliant minds who dared to dream them up.